Scott Alexander has an article at Slate Star Codex discussing the use of edge cases in moral philosophy:

There’s a tradition at least as old as Kant of investigating philosophical dilemmas by appealing to our intuitions about extreme cases. Kant, remember, proposed that it was always wrong to lie. A contemporary of his, Benjamin Constant, made the following objection: suppose a murderer is at the door and wants to know where your friend is so he can murder her. If you say nothing, the murderer will get angry and kill you; if you tell the truth he will find and kill your friend; if you lie, he will go on a wild goose chase and give you time to call the police. Lying doesn’t sound so immoral now, does it?

This is a great way of doing philosophy, but reading it, I realized I had heard it before. I’ve heard this sort of argument in the context of policy debates.

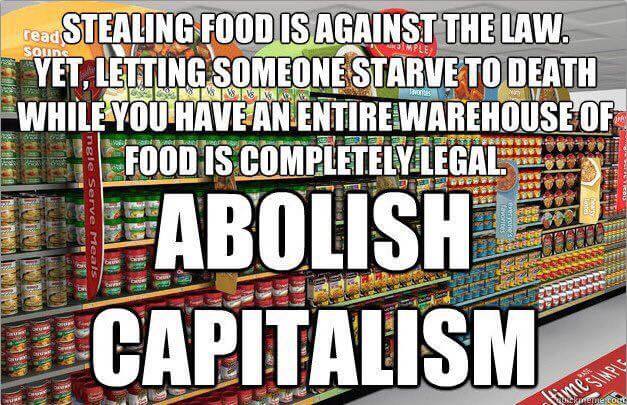

Here’s a particularly striking example (h/t to Jason Brennan):

Unlike the case of the door-to-door murderer, which is a deliberately fanciful way of examining a broader moral truth, this is a policy proposal made on the basis of a fanciful scenario. The argumentation goes like this:

- In an unlikely scenario, economic system A would allow bad outcome X

- Therefore, abolish A (and substitute it with another system, such as B)

There are a lot of errors packed into this line of thinking. What if bad outcome X happens under both systems? What if changing systems just substitutes bad outcome Y for X? What this fails to do is compare the relevant alternatives. Is the implicit claim that under socialism, nobody would ever starve? Millions of Soviet citizens beg to differ. Continue reading The Trolley Car Approach to Public Policy