Today’s guest is Stephen Smith, he is an analyst for a New York real estate firm.

Stephen did some research showing that at least 40 percent of the buildings in Manhattan could not be built under today’s zoning regulations. In fact, the number is probably significantly higher. Classic landmarks like the Empire State Building, with its floor-area ratio of 30, wouldn’t fly today.

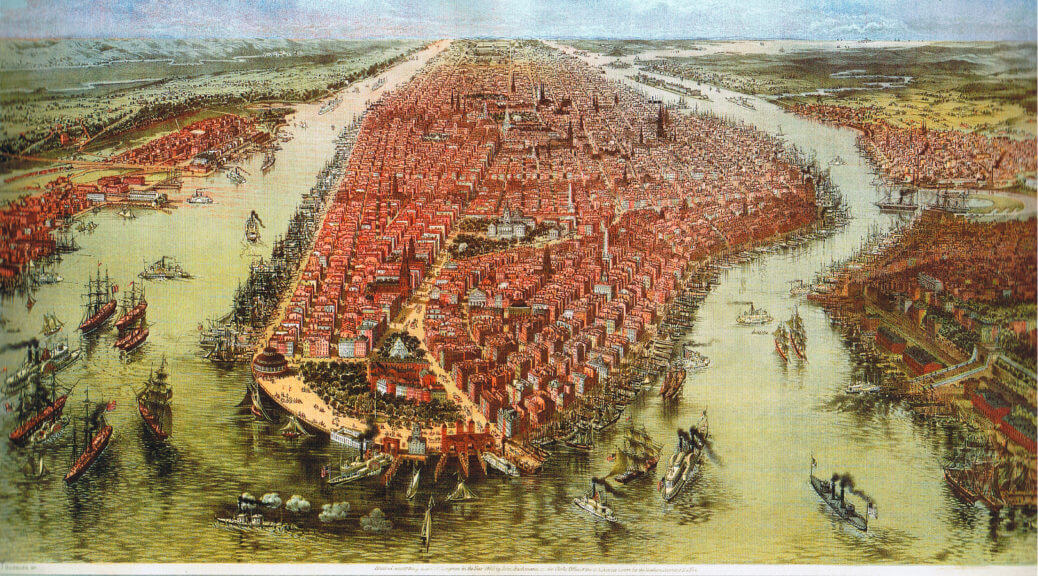

Watch this time-lapse of the New York City skyline, and pay close attention to the kind of changes that happen in the earlier part of the video compared to the later part:

Before the twentieth century, the pace of change is very gradual. Two storey buildings are replaced with three storey buildings. Waves of development sweep through the city, replacing wood buildings with brick and stone and concrete.

In the twentieth century, we see a different kind of development. Pay attention to any particular small building and you’ll notice one of two things happening: Either the building stays exactly as it is, or it is replaced by a massive skyscraper. There’s no more gradual change.

This is caused by the city’s adoption of land-use regulations. The first zoning code was adopted in 1916, but the really strict zoning came in 1961. Once this happened, tearing down and replacing a building meant pulling political strings to get it rezoned. Because of the significant fixed cost of getting a lot rezoned, developers opted to build a few extremely tall buildings rather than many moderately tall ones. Heavy restrictions in most of Manhattan led developers to concentrate development in the few places that would allow it. That’s why Midtown built up while other neighbourhoods didn’t.

New York’s mayors tend to be pro-development, but its city councillors block development at every turn. The city council’s behaviour is consistent with William Fischel’s home voter hypothesis. The city council tends to defer to individual councillors on their own local issues, giving each councillor de facto control over development in his neighbourhood. When authority is devolved to the hyper-local level, there’s a strong incentive to block development to raise real estate prices.

Download this episode.

Subscribe to Economics Detective Radio on iTunes, Android, or Stitcher.