My guest for this episode is Noel Johnson of George Mason University, and if that name sounds familiar, it’s because he was the coauthor on the paper I discussed with Mark Koyama last month.

Noel recently released a working paper titled “The Effects of Land Redistribution: Evidence from the French Revolution.” It is co-authored with Theresa Finley and Raphael Franck. The paper examines the consequences of the land auctions held by the Revolutionary government in France. The abstract reads as follows:

This study exploits the confiscation and auctioning off of Church property that occurred during the French Revolution to assess the role played by transaction costs in delaying the reallocation of property rights in the aftermath of fundamental institutional reform. French districts with a greater proportion of land redistributed during the Revolution experienced higher levels of agricultural productivity in 1841 and 1852 as well as more investment in irrigation and more efficient land use. We trace these increases in productivity to an increase in land inequality associated with the Revolutionary auction process. We also show how the benefits associated with the head-start given to districts with more Church land initially, and thus greater land redistribution by auction during the Revolution, dissipated over the course of the nineteenth century as other districts gradually overcame the transaction costs associated with reallocating the property rights associated with the feudal system.

What’s so interesting about this particular instance of land redistribution is the fact that it was all sold to the highest bidder rather than being given to the poor. This breaks the pattern of most attempts at land reform throughout history. People have been trying to take land away from the rich and give it to the poor since at least Tiberius Gracchus in the second century BCE. But the Revolutionary government needed money and they needed it fast. So they concocted a plan to seize and auction off all French lands owned by the Catholic Church, which comprised about 6.5 percent of the country.

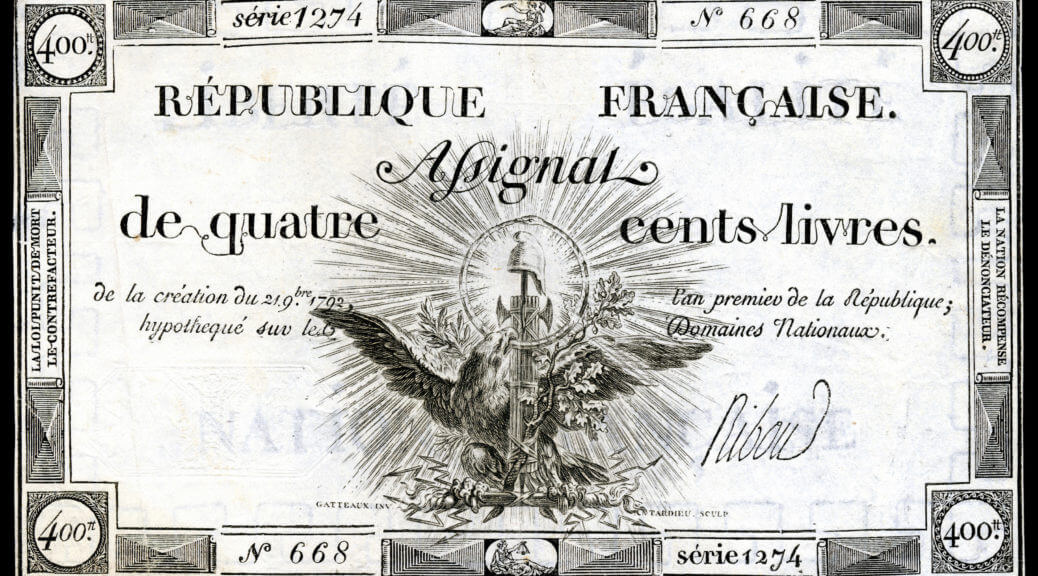

Land auctions take time though, and the government desperately needed funds in the short term, so they issued a monetary instrument known as the assignat that could be used in these land auctions. The land was eventually auctioned off and then traded in secondary markets, where much of it was consolidated into large estates that could employ capital-intensive agricultural practices on a large scale.

The evidence suggests that these land auctions added to the productivity of the regions where they occurred. Noel argues that this occurred because the reduction in transaction costs allowed for a more efficient allocation of property rights. One could argue, however, that the Church might have simply owned more productive land to begin with, and the paper uses a series of identification strategies to show that this is not the main driver of their results.

Related Links:

McCloskey (1998) on the Coase theorem.

Gallica, the website where you can download a ton of digitized French archives.

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2005) on Atlantic trade.

Rachel Laudan discusses the history of potatoes and other foods on EconTalk.

Photo credit: Early French banknote issue during the French Revolution (Assignat) for 400 livres, (1792), from the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.

Subscribe to Economics Detective Radio on iTunes, Android, or Stitcher.