Knowledge of the effects of government interference with market prices makes us comprehend the economic causes of a momentous historical event, the decline of ancient civilization.

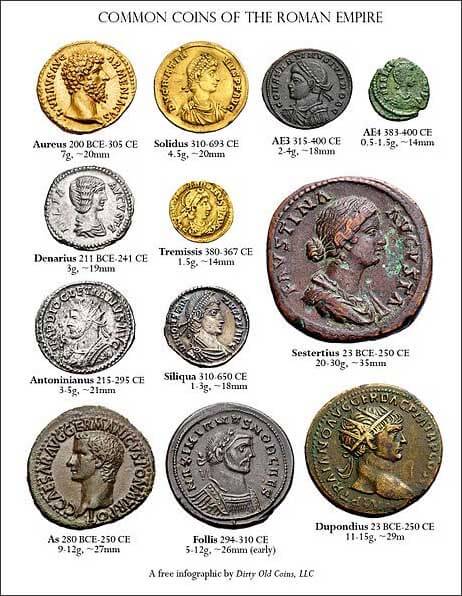

It may be left undecided whether or not it is correct to call the economic organization of the Roman Empire capitalism. At any rate it is certain that the Roman Empire in the second century, the age of the Antonines, the “good” emperors, had reached a high stage of the social division of labor and of interregional commerce. Several metropolitan centers, a considerable number of middle-sized towns, and many small towns were the seats of a refined civilization. The inhabitants of these urban agglomerations were supplied with food and raw materials not only from the neighboring rural districts, but also from distant provinces. A part of these provisions flowed into the cities as revenue of their wealthy residents who owned landed property. But a considerable part was bought in exchange for the rural population’s purchases of the products of the city-dwellers’ processing activities. There was an extensive trade between the various regions of the vast empire. Not only in the processing industries, but also in agriculture there was a tendency toward further specialization. The various parts of the empire were no longer economically self-sufficient. They were interdependent.

What brought about the decline of the empire and the decay of its civilization was the disintegration of this economic interconnectedness, not the barbarian invasions. The alien aggressors merely took advantage of an opportunity which the internal weakness of the empire offered to them. From a military point of view the tribes which invaded the empire in the fourth and fifth centuries were not more formidable than the armies which the legions had easily defeated in earlier times. But the empire had changed. Its economic and social structure was already medieval.

The freedom that Rome granted to commerce and trade had always been restricted. With regard to the marketing of cereals and other vital necessities it was even more restricted than with regard to other commodities. It was deemed unfair and immoral to ask for grain, oil, and wine, the staples of these ages, more than the customary prices, and the municipal authorities were quick to check what they considered profiteering. Thus the evolution of an efficient wholesale trade in these commodities was prevented. The policy of the annona, which was tantamount to a nationalization or municipalization of the grain trade, aimed at filling the gaps. But its effects were rather unsatisfactory. Grain was scarce in the urban agglomerations, and the agriculturists complained about the unremunerativeness of grain growing.* The interference of the authorities upset the adjustment of supply to the rising demand.

The showdown came when in the political troubles of the third and fourth centuries the emperors resorted to currency debasement. With the system of maximum prices the practice of debasement completely paralyzed both the production and the marketing of the vital foodstuffs and disintegrated society’s economic organization. The more eagerness the authorities displayed in enforcing the maximum prices, the more desperate became the conditions of the urban masses dependent on the purchase of food. Commerce in grain and other necessities vanished altogether. To avoid starving, people deserted the cities, settled on the countryside, and tried to grow grain, oil, wine, and other necessities for themselves. On the other hand, the owners of the big estates restricted their excess production of cereals and began to produce in their farmhouses–the villae–the products of handicraft which they needed. For their big-scale farming, which was already seriously jeopardized because of the inefficiency of slave labor, lost its rationality completely when the opportunity to sell at remunerative prices disappeared. As the owner of the estate could no longer sell in the cities, he could no longer patronize the urban artisans either. He was forced to look for a substitute to meet his needs by employing handicraftsmen on his own account in his villa. He discontinued big-scale farming and became a landlord receiving rents from tenants or sharecroppers. These coloni were either freed slaves or urban proletarians who settled in the villages and turned to tilling the soil. A tendency toward the establishment of autarky of each landlord’s estate emerged. The economic function of the cities, of commerce, trade, and urban handicrafts, shrank. Italy and the provinces of the empire returned to a less advanced state of the social division of labor. The highly developed economic structure of ancient civilization retrograded to what is now known as the manorial organization of the Middle Ages.

The emperors were alarmed with that outcome which undermined the financial and military power of their government. But their counteraction was futile as it did not affect the root of the evil. The compulsion and coercion to which they resorted could not reverse the trend toward social disintegration which, on the contrary, was caused precisely by too much compulsion and coercion. No Roman was aware of the fact that the process was induced by the government’s interference with prices and by currency debasement. It was vain for the emperors to promulgate laws against the city-dweller who “relicta civitate rus habitare maluerit.”** The system of the leiturgia, the public services to be rendered by the wealthy citizens, only accelerated the retrogression of the division of labor. The laws concerning the special obligations of the shipowners, the navicularii, were no more successful in checking the decline of navigation than the laws concerning grain dealing in checking the shrinkage in the cities’ supply of agricultural products.

The marvelous civilization of antiquity perished because it did not adjust its moral code and its legal system to the requirements of the market economy. A social order is doomed if the actions which its normal functioning requires are rejected by the standards of morality, are declared illegal by the laws of the country, and are prosecuted as criminal by the courts and the police. The Roman Empire crumbled to dust because it lacked the spirit of liberalism and free enterprise. The policy of interventionism and its political corollary, the Fuhrer principle, decomposed the mighty empire as they will by necessity always disintegrate and destroy any social entity.

*Cf. Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire (Oxford, 1926), p. 187.

**Corpus Juris Civilis, 1. un. C. X. 37.

Here’s a passage from

Here’s a passage from